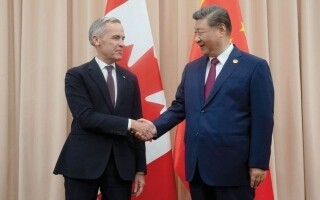

Following Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney's speech at the latest Davos forum, all of Europe was thrown into anxiety. Carney described the rules-based system, long championed by Washington, which the US now 'tramples on,' as an illusion, and sharply criticized American hegemonism, leaving Europeans perplexed. However, before European politicians rush to echo him, it might be wise to temper the enthusiasm for Carney. At the World Economic Forum in Switzerland, Carney, who appeared stern in his address, warned medium-sized powers: 'When we negotiate bilaterally with a dominant power, we do so from a position of weakness.' This may have been an allusion to the daily pressure Canada faces from the US administration, but perhaps he was referring to a more precise contrast he had experienced just days earlier in China's capital, Beijing. Unlike the challenge thrown down in Switzerland, Carney was 'accommodating' during his visit to China, where he signed a 'new strategic partnership' between Ottawa and Beijing in preparation for an 'emerging new world order,' and praised Chinese President Xi Jinping as a fellow defender of what he called 'multipolarity.' The visit also resulted in a vehicle-for-canola agreement: Canada will reduce tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles from 100% to 6.1% and raise the import cap to 49,000 vehicles per year. In return, China will reduce tariffs on Canadian canola from 84% to 15%. Over time, Ottawa also expects China to reduce tariffs on Canadian crab, lobster, and peas later this year and buy more Canadian oil, and possibly gas as well. Undoubtedly, agreeing to launch a ministerial dialogue on energy will pave the way for deals to be struck eventually. These fruitful exchanges ultimately led Carney to declare Beijing a 'more predictable trading partner' than Washington. And who can blame him? He was simply stating the obvious: after all, China does not threaten Canada with annexation, as the US does. Yet, some observers wonder if he needed to flatter China so much if his country still possessed some of the world's leading technology. Rapid Change. The truth is, perhaps not much should be expected from Canada's oil and gas industry. Chinese officials typically offer serious consideration rather than outright rejection, motivated solely by 'goodwill.' Russia is an example of this: Moscow spent decades in dialogue with Beijing over a pipeline aimed at replacing Europe as a market for natural gas. The vehicle-for-canola deal also contains an element of irony: Canada is importing the very same technology that makes fossil fuels obsolete. China is rapidly shifting to electric energy, and the International Energy Agency expects its oil consumption to fall significantly as early as next year thanks to 'exceptional' electric vehicle sales. This means Beijing may not desperately need new foreign suppliers of petroleum products, and the ministerial dialogue will likely continue politely without result for a long time to come. China-Canada trade can be seen as a classic case of comparative advantage: China is good at making things, and Canada has abundant primary commodities. But not so long ago, Canadian companies were selling nuclear reactors, telecom equipment, airplanes, and high-speed trains to China. Now, however, many of these once-world-leading Canadian tech manufacturers have either exited the stage or operate with extreme limited capacity. The Momentum of Manufacturing. Somewhere in the history of this trade lies a cautionary tale for Europe. Manufacturing can have its own momentum, and as a country's economic makeup changes, so does its political economy. When producers of goods disappear, their political influence disappears too, and the center of political gravity shifts towards end-users and consumers who prefer readily available imports. Europe already has its own version of this story: over two decades, cheaper Chinese products pushed local solar panel manufacturers to the brink of extinction. Today, the solar energy industry is dominated by installation and operation firms that prefer cheap imports. Simply put, Carney's vehicle-for-canola deal is a balm for Canadian consumers and primary producers, but it is also a reverse industrial policy. Trade Shock. In the simplest terms, industrial policy aims to encourage the export of finished goods over raw materials to build domestic capacity and productivity. But while Canada may be able to afford to forgo industry, as Carney suggested in Davos, its ambition is to be an 'energy superpower.' Europe does not have this option, and even with the addition of sectors like tourism and luxury goods, the continent's agricultural and extractive sectors are not enough to support its economy. China currently exports more than twice as much to the European Union as it imports, and Goldman Sachs estimates that Chinese exports will reduce Germany's, Spain's, and Italy's GDP growth by 0.2 percentage points or more each year until 2029. According to the European Central Bank, the automotive, chemical, electrical equipment, and machinery sectors, which form the industrial backbone of Europe, are facing the largest job losses due to the 'Chinese trade shock.' A Sharper Challenge. Europe shares Canada's problem of dealing with the United States, which is now not just an unreliable trading partner but an ally that has turned into a 'hegemon.' For this reason, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney's speech in Davos resonated widely. However, American protectionism has only made China's economic policy a sharper challenge for Europe, as the US resists the EU's exports while Chinese goods continue to flow into Europe in larger volumes and at lower prices. It would be a mistake for European leaders to seek to alleviate trade pressure with China's help, as Carney is doing, and in the process, to cede the continent's industrial capacity. Whether to resist Russia or the United States, Europe still needs to hold on to its industrial base.